A look at the most important historical sites in Sant Feliu de Guíxols.

The area around Sant Feliu de Guíxols has been populated since pre-historic times with an Iberian settlement founded some time in the 5th century BC. Later the Romans colonised the area and in the middle ages the Benedictine monastery was founded, prompting further population growth.

Over centuries that followed the town would expand thanks to the cork industry and shipbuilding. But it also suffered from plagues, famine, pirate attacks and wars, including the 1936-1939 conflict in Spain between Franco’s forces and the Republicans. Visit the sites below and you’ll get a great idea of Sant Feliu’s rich history.

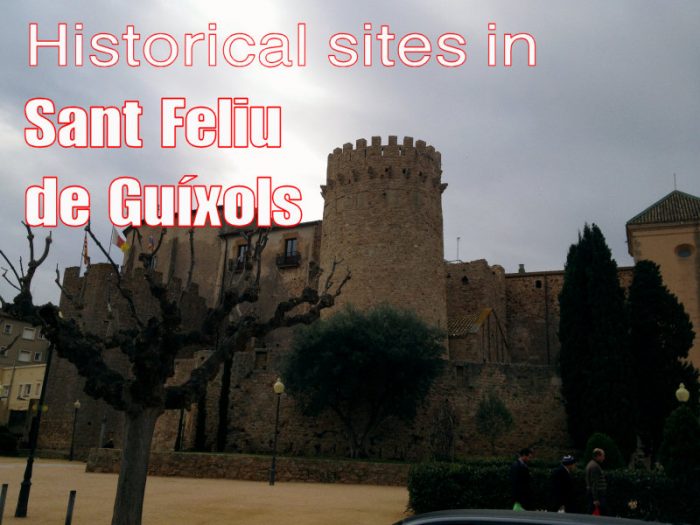

Monastery

Carrer del Monestir, 1

The earliest surviving reference to Sant Feliu’s Benedictine monastery date to the tenth century. Built on previous Roman buildings, the site was chosen because of the natural harbour and the protection offered by nearby hills.

The monastery in Sant Feliu de Guíxols (Kippelboy)

The monastery was built to help repopulate the area by offering protection to inhabitants in exchange for working the land. The area was frequently attacked by pirates from North Africa in a time prior to the vast wealth that was to come from the sea.

The oldest part of the monastery is known as Porta Ferrada, which forms the façade of the Romanesque church of Mare de Déu dels Àngels. Porta Ferrada connects two towers and is named after the iron door of the church.

The façade of Porta Ferrada (Joan Vila)

The Torre del Fum – smoke tower – dates from tenth century on the ruins of fifth century building. In the case of attack it warned distant settlers by a plume of smoke. The Torre de Corn – horn tower – dates from the tenth and eleventh century and raised the alarm to by sounding a horn to those closer by.

The monastery was fortified in the 14th century with five towers and modified substantially over the centuries. The most recent substantial addition is the large baroque section dating from the 18th century. Not everything has survived though, such as the buildings that once surrounded Porta Ferrada. The latter has been extensively renovated to the condition in which you find it today.

Once the entrance to the monastery complex whose walls are long gone, the baroque-style Sant Benet Arch stands alone. Completed in 1747, the original statue at the top of the arch was destroyed during the civil war. The replacement dates from 1999.

Sant Benet arch with the replacement statue (Mutari)

Hospital

Carrer de l’Hospital, 33

Walk a short distance from the monastery and you’ll find Sant Feliu’s former municipal hospital. A hospital was first constructed on this site at the turn of the 17th century.

However the neoclassical design dates from renovations in the mid 19th and early 20th centuries. Comprising of two floors, there is a chapel on the right with a large courtyard behind.

The old municipal hospital (Wikiaps)

When it was built it was located outside the city walls, replacing an older hospital within the walls. The reason for its placement was to avoid contagious diseases to spread within Sant Feliu. It also had a nursery school, a courtyard and a chapel.

It was also used as an Augustinian convent but this created conflict with the nearby Benedictine monastery. The Benedictines claimed rights to the land on which it was built and the abbot pressurised the Bishop of Girona to intervene. Although he eventually expelled the Augustinians the hospital continued to serve the town.

The hospital struggled with the age old problem of funding. A small number of sizeable donations in the mid-18th century helped though and while it still struggled financially more donations kept it operational.

Casino la Constància

Rambla del Portalet, 1

One of the most distinctive buildings on the promenade is the Casino de Constància. Designed by Catalan modernist architect General Guitart i Lostaló, the casino was constructed between 1888-1890.

The distinctive architecture of Casino de Constància (David Leigh)

Anyone expecting to play roulette or a high stakes game of poker will find themselves disappointed though. In Spain a casino is a social club rather than a gambling house. Visitors may play cards or dominoes but it’s not the kind of place you might find James Bond.

Two houses on the corner of Rambla del Portalet and Carrer Sant Roc were bought and demolished in order to make way for the casino, which features Arabic style doors with a horseshoe arch and circular corner turret. Locally it is often referred to as casino dels nois, referring to the progressive youngsters who developed the casino as a cultural centre.

These days you can grab a coffee there, sip a beer or get a bite to eat.

Indianos houses

A number of Costa Brava towns did well out of trading with the New World, particularly Cuba, Venezuela and Puerto Rico. Local cork and wine were exported, while boats returned laden with sugar, coffee, cotton and tobacco.

Those who had made their fortunes in the Americas were often known locally as indianos or americanos. When returning home they often built spectacular houses to show off their newfound wealth. Perhaps the most visible are on the promenade at Sant Pol beach.

Casa Girbau Estrada on the promenade at Sant Pol (David Leigh)

There were a number of examples on Passeig de Guíxols. While many of these made way for apartment buildings in the latter part of the 20th century thanks to tourism-inspired real estate speculation a number of still remain, including Casa Patxot, which is on the corner opposite Casino la Constància. One detail sometimes glossed over is that some indianos owed part of their wealth to the slave trade.

Old railway station

Carrer Santa Teresa, 49

Until 1969 Sant Feliu was joined to Girona by a narrow gauge railway. The line allowed Girona’s inhabitants to escape the oppressive summer heat and spend a day by the sea. Later it was extended down to the port area in order to load and unload goods. The old station dates from 1892 and is now part of a school.

Port

Unlike many Costa Brava towns Sant Feliu de Guíxols still has a working port.

The port area of Sant Feliu de Guíxols at dusk (David Leigh)

Down here you’ll find an old railway shed, now a El Tinglado restaurant and museum. The shed dates from when the railway was extended to transport cork and other goods and now has a steam engine and photographs from the era when the railway was operating. There was also a turntable used to turn the engines around for their return to Girona.

You’ll also find the yacht club down here and during the summer the Porta Ferrada Festival takes place here with a temporary stage and seating.

Market square

Plaça del Mercat

A weekly open air food market takes place in the market square every Sunday while the promenade has stalls selling clothing and other items.

The market square (David Leigh)

Overlooking the square, just a short distance from the town’s main beach, is the gothic style town hall. The main building dates from 1547, with a tower added in 1847.

Next to the market square is an indoor food market dating from the 1930s. Open between 8:30am and 1:30pm daily, the market building was restored in 2011 and has a first floor is a bar/restaurant.

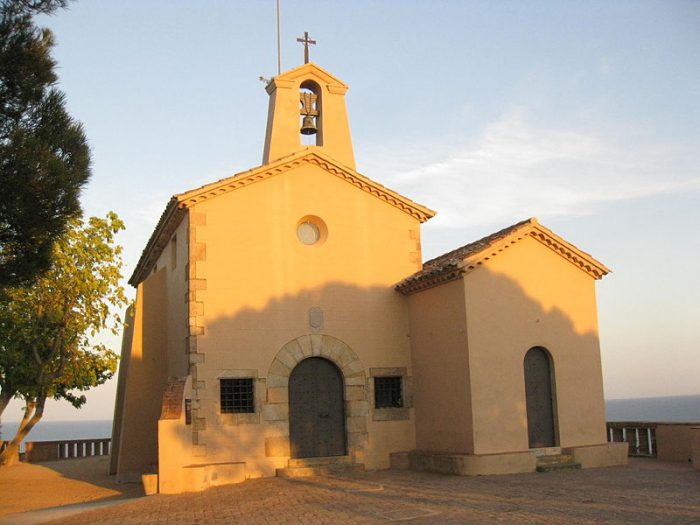

Hermitage Sant Elm

Av. Sant Elm, 12

Ferran Agulló is credited with being the first to refer to this coastline as the “Costa Brava” in an article published in September 1908. The Catalan journalist, poet, gastronome and politician was a Sant Feliu native and is said to have coined the phrase after visiting Sant Elm with friends, inspired by the spectacular views.

Ermit de Sant Elm (Enfo)

Situated on the peninsula southwest of Sant Feliu, from the hermitage you can see for miles down the coast, look out over the great expanse of sea, look over Sant Feliu, or inland towards the cork covered hills.

There has been a chapel on this site since 1452 although fortifications were constructed here in the early 13th century. After chapel and fortifications were destroyed by the French in the late 17th century a new chapel was constructed in in 1723. The current chapel is the result of restorations in 1943 and 1993.

Opening hours are limited to guided tours offered by the local tourist board.

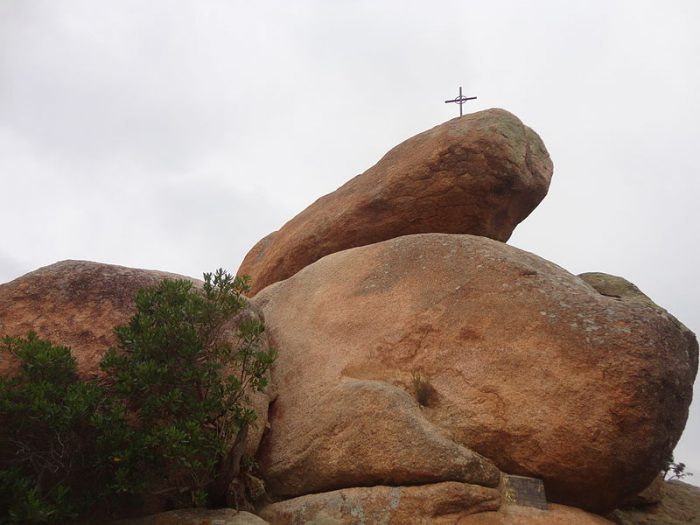

Pedralta

In the hills above Sant Feliu you can find what at one time was the largest rocking stone in Europe, topped by a cross.

The 101 tonne Pedralta sits atop a 17 metre high rock formation (Arnaugir)

Pedralta is precariously perched at the top of a 17 metre high rock formation and, despite weighing in at 101 tonnes, was capable of being rocked by hand.

Unfortunately a 1996 storm saw it topple to the ground and when it was repositioned three years later using two cranes it was fixed in place rather more securely – it no longer rocks.

Bomb shelter

Carrer Penitència/Carrer dels Metges

It’s perhaps hard to believe that anywhere on the Costa Brava should be the target of bombardment from sea and air, but during the Spanish Civil War the Costa Brava did come under attack. Like most of Catalonia, Sant Feliu was staunchly behind the democratically elected Republican government. It was to become one of the coastal towns to be have the most casualties.

On 7th June 1937 the town was shelled by the Nationalist flagship, the cruiser Canarias. By 6th February 1938, days after an air raid by Italian forces, the local defence committee (source: page 205) reported that the town had suffered a total of 12 air raids and 2 from the sea, killing 26 people and injuring 80 more. 200 bombs and 21 shells fell on the town and in addition to the dead and injured 22 houses were destroyed and 343 damaged.

By the end of the war the total attacks numbered 37 with around 70 dead and 130 injured. 50 building were destroyed and around 600 more damaged.

Refugi del Puig is a surviving bomb shelter. Cut into the rock, the shelter was rediscovered in 2010 during construction work in the Puig district of Sant Feliu, with the entrance uncovered three years later. Work began shortly after that first bombardment by the Canarias and continued until 1938.

To arrange a visit to the shelter you need to get in touch with the town’s museum at least 15 days before the planned visit.